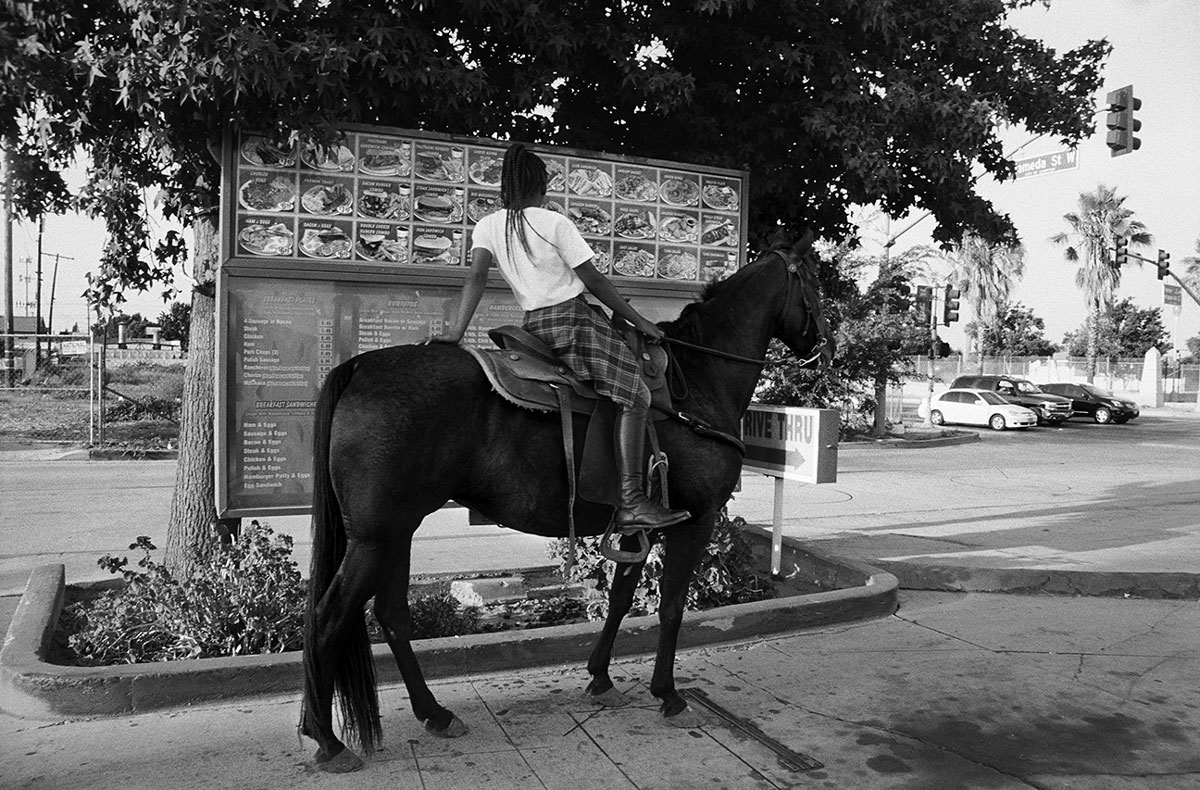

Put a horse on a city street and it changes the place. Cracks appear under its hooves, and the earth that still lives and breathes below is suddenly talking again. The people are changed, too, suddenly conversant with the blowing and snorting of horses and the wind in the palm trees and the sun flying above, affirmed and lifted in our belonging to a bigger natural community.

Melodie McDaniel’s photographs capture that sense of belonging to place and community. For the last several months at LA HOMEFARM, we’ve been privileged to show her photographs of riders and horses from the equestrian clubs of the city of Compton, in South Los Angeles, in a show she’s called “Daring to Claim the Sky.”

Compton is a place that’s been paved over for decades, an urban environment where the struggles are also urban, a place of concrete and cars and fast food and single-family homes with a strong working-class community and, like a lot of LA, a stubbornly high number of families in poverty.

Kenneth with Pirate, 2017. Photograph by Melodie McDaniel

And yet, there are horses and their power to transform identity. In 2015, Melodie started hanging out with two clubs, the Compton Jr. Posse – now known at the Compton Jr. Equestrians – and the Compton Cowboys. Two different groups with different missions: the Equestrians focus on English dressage and jumping, while the Cowboys are into Western riding, though there are some riders who do both. The connection was through a friend, writer Amelia Fleetwood Simpson, whose husband, Olympic gold-medal winning horse jumper and coach Will Simpson, was helping to train the Jr. Possee. He introduced Melodie to legendary Jr. Posse founder, Mayisha Akbar.

“It’s not just for African Americans. It is, predominantly, but there are Latino kids that go there. They welcome all,” says Melodie, interviewed in December in a Glassell Park coffee shop. “Mayisha started it [in 1988] after she moved to Compton, as an activity for her own son and some of the other kids in that area. She brought horses with her when she moved there, and there are other families that have horses in their backyards, too. But she didn’t realize the gangs and stuff was going on until she settled in there. She talked a lot about how the responsibility of taking care of a horse was full of life lessons, even beyond keeping the kids off the streets. More than just riding, they learn the value of education and staying in school. Her emphasis is to teach the kids about competitive riding, horse care, and going on to college.”

Mayisha’s mission, as she liked to say, was “Keeping kids on horses and off the streets.”

Horses are the last thing anyone would expect in Compton, but that’s partly because we don’t really know the place. The city stormed onto the cultural map in the late-1980s with the hard-hitting gangsta rap of NWA’s debut, Straight Outta Compton, a group put together by Crip gang member Eric “Eazy E” Wright. NWA created a genre with its powerful, furious, lyrically devastating tracks depicting a reality of crack cocaine dealing and violence. The group transformed American music and stamped an image on that city. For most of America, “gangsta” is all Compton has ever been, and almost every article about the equestrian clubs there emphasizes the power of horses to keep young people out of the gang life. The Compton Cowboys make it part of their branding: “Streets raised us. Horses saved us.” That power to reclaim identity is a product of the riders’ grit and determination to transform their own lives – and it also flows directly out of contact with the earth, surfacing an ongoing relationship to agriculture and the land that is still informing Compton and is all but invisible to the outside world.

Melodie McDaniel. Photograph by Len Peltier

The city of Compton was created with the express intent to support agriculture. When Spain controlled Southern California in the 1700s, the crown granted the area now known as South LA to a former Spanish soldier and it was known as (among other names) Rancho Dominguez. White settlers led by Griffith Compton settled the area in 1867, and it was incorporated in 1888. Compton donated his land to help create the city, but stipulated that a large part of it be set aside as agricultural. That area is known as Richland Farms, which is still part of Compton today.

The large lots in Richland Farms were like ranchettes, where owners could live and put up a barn and raise livestock and crops. African Americans migrating out of the South after World War II found Richland Farms was a place they could raise families and continue agricultural traditions they brought with them. In the 1990s, Latino families migrating out of Mexico and Central America were attracted to Richland Farms for the very same reason.

Erika Cuellar and Richard Garcia started Alma Backyard Farms on the former ball fields at Compton’s St. Albert the Great Catholic Church, just a few blocks north of the Richland Farms area, growing beautiful organic produce there as a project to re-integrate formerly incarcerated folks back into the community. On one of my visits there, both of them noted to me that residents who visit their Sunday produce market share how their relatives or friends used to have farm plots in Compton, and how they remember Richland Farms and other spots in the city as being places where a proud people could feed themselves. Both the Compton Cowboys and the Compton Jr. Equestrians are headquartered in Richland Farms. The agricultural heritage and traditions of Compton are alive and asserting themselves today.

Melodie first showed these photos in 2018 and published a gorgeous book the same year, “Riding Through Compton.” In an intro to the book, Mayisha Akbar wrote about her motivations for the club: “I grew up in the housing projects of Harbor City, California [a suburb of LA a little further south], which at that point were surrounded by agriculture. There were horses, cows, and crops in the middle of where we lived, and that’s where I always went to entertain myself. A few neighbors had horses that we rode with no saddles or bridles or anything – we would just get on and ride around with no instruction. It was a wonderful memory. I wanted to recreate this feeling of freedom for my own children…..”

Since that time, the Getty Museum, Vasser College and the Portland Art Museum in Oregon have acquired a number of these images. Even now, not many people are aware these clubs exist. Melodie keeps up with the riders’ progress.

“I am still in touch because, man, there’s still more great stories that are happening from this. Some of them are about to go into college, and one wants to apparently go to the Olympics,” Melodie says.

Melodie knows a thing or two about the search for belonging and identity. We’ve been friends for more than 25 years, and I’ve watched her use her work to find a place for herself in pop culture, fashion, cultural currents and even within her own family. She was born in Omaha to a loving and hard-working Jewish mother and a dad who was Black jazz guitarist who was in and out of their lives. Melodie was only one or two years old when her mom moved to Los Angeles to find work, so she and her two siblings grew up as Angelenos.

She was on her second trip to Israel, working on a kibbutz at age 18, when she realized photography might be a way for her to process what was becoming of her life. She was harvesting bananas in the hours before dawn, chopping the stalks with a heavy knife and dealing with big spiders and insects that lived on them, when she grasped that no other kid she knew from LA was living like this. Growing up in the 1970s and ‘80s, she was a product of a contemporary urban culture, but also a part of this ancient world.

“Going to Paris, London, Italy, all those things are beautiful and interesting, but when you go to the Middle East, you really feel like, ‘Oh my God. This is the beginning of time,’” she says.

She picked up a camera and took a class at Technion, an Israeli technology school, with an architectural photographer who let Melodie tag along as she did her work. She ended up studying at Art Center in Pasadena, and along the way met Len Peltier, an art director at A&M Records, who gave her a first big break, shooting album art for Sheryl Crow’s 1993 debut record. Melodie worried that she didn’t really nail that assignment, dragging Sheryl around the dusty desert town of Baker, CA, but that was the start to her professional journey.

She and I first worked together only a year or so later, on a story about the Black Crowes. Maybe crows are a sub-theme, here. I was editing a magazine called huH, part of the family of magazines put out by Ray Gun Publishing and designed by the late and extraordinary Vaughan Oliver. Melodie and I met the Black Crowes at a rehearsal studio in Hollywood, where they treated us to a searing rendition of their new song, “Gone,” and I found new admiration for guitarist Rich Robinson. Afterward, Melodie walked them around outside in the stifling heat and shot them against the weird, sunburnt dilapidation of 1990s Hollywood, a landscape of windblown trash and broken-down front porches and ponytail palms. I was new to the air of destruction and burned dreams that attends that place and watched the homeless and every passing car for signs of interference or trouble. But for Melodie, this was her back yard; she could go anywhere here, smiling, joking, and no one would mess with her.

That same year, she directed a PSA for Nike featuring Michael Jordan, and was then tapped to make the video for Madonna’s “Secret.” She set the production in Harlem. From Melodie’s description of that time, it seems Harlem was a place they both needed to encounter and understand: Madonna, the hitmaker, hungrily devouring cultures, depicted in the video as the only white woman in a smoky, bluesy Black night spot, in a pool hall, on the streets; Melodie, a Black artist, living for a time in NYC and making her own peace with those clubs and streets where musicians like her father would struggle and reinvent music on a nightly basis and probably never have hits or make much money.

Melodie’s dad followed them to LA, where he worked a blue-collar job at UCLA and lived apart from the family. She saw him jamming a little with musician friends now and then, but he wasn’t really working in music at that time and she didn’t know much about his artistic life. She saw him struggling, and around 1990 he moved back to Omaha. He passed away in 2017 and she’s still searching for more information about his life.

“My mom is so strong,” Melodie says. “She was always there for us.”

Raising the kids alone, Melodie’s mom has been a powerful influence in her life – signing her up for cultural programs, making fun, teaching her about art and at least one side of her ethnic and religious life. She always worked multiple jobs so she could give the kids experiences like travel to Israel. But it seems every community has its self-imposed confines: some people in Israel asked Melodie what she was doing there, since it wasn’t obvious that an American Black woman might also be Jewish.

Imagine the joy, then, of seeing Black and Latino kids stake out their own identities on the back of a horse. Melodie figured out that you can make your own path and find your own family.

I know and love a lot of hers. In the course of a big career that has included short films; music videos for Smashing Pumpkins, Cat Power, Pharrell Williams and My Morning Jacket, among many others; over 200 advertising campaigns for clients from Nike to Chrysler to Chanel; and editorial for GQ, Time, L’Uomo Vogue, and other publications, she has gathered around her a family of artists, actors, production folks and great humans. Some of those ties are as strong as blood.

She gives special focus to documentary projects like “Daring to Claim the Sky.” Before the shoots in Compton, she traveled to Rwanda and Ethiopia to photograph a project for the Nike Foundation called “The Girl Effect,” photographing young women at their most open moments, learning about their dreams.

“I always loved the early stuff that Annie Leibovitz shot, the documentary work, running around with Hunter S. Thompson,” Melodie notes. “I keep going back to Gordon Parks, Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson, Diane Arbus, and William Eggleston, the master of color.”

These are photographers who helped define us. Davidson’s shots from Harlem, the Civil Rights struggle, white teen-aged Brooklyn gang members. Parks’ world-changing photos of Black life. Arbus’s deeply humanizing portraits. Eggleston’s diners and filling stations and cars and the people in them. Frank’s stunningly surprising moments of human drama in cities and small towns. Leibovitz’s shots of Thompson in discussion with Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern, or workers rolling up the carpet after Nixon’s resignation. Like so many of these, Melodie’s documentary work seeks out America the way it sees itself, a national identity that happens always in a place, defined by neighborhoods, churches and, yes, races and ethnicities.

She is currently working on a film about a religious community in Appalachia. You can be sure the results are doing to take us in a little deeper, and show us a little bit more about who we are as human beings. A place and its flora and fauna also change the way we talk to God. And so, in Melodie’s hands, the families to which we all belong expand to include horses and the next-door neighbors and sky and earth and who knows what else. Daring us to claim them.

By Dean Kuipers

Drive Thru, 2017. Photograph by Melodie McDaniel